In his groundbreaking 1972 book Victims of Groupthink, research psychologist Irving Janis examines three case studies: the United States’ failure to anticipate the Pearl Harbour attacks, the Vietnam War, and the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion. Had he written his book a few decades later, Janis may have been tempted to include a few examples from the corporate world, such as Xerox voluntarily giving away its graphical user interface to Apple in exchange for some shares of Apple stock, Kodak suppressing the digital camera that it had invented in order to focus on selling soon-to-be-obsolete celluloid, and Excite turning down a $750,000 offer to buy a little known start-up called Google.

What each of these examples has in common is that they all involve large groups of very smart people making inexplicably poor decisions. Xerox, for instance, is a company that employs over 100,000 people. Surely at least one of them recognized the potential of the GUI to spawn the trillion dollar business we now know as the computer industry?

As it happens, more than a few employees did. In his biography of Steve Jobs, Walter Isaacson describes how one enterprising Xerox employee, in a scene that plays like something out of a sitcom, cleverly tried to hide the GUI from Jobs and his Apple associates while giving them a tour of the Xerox premises. Unfortunately for Xerox, these efforts were thwarted by upper management, who remained dead set on giving their game-changing technology away. The company was confident in the belief that it would forever hold a monopoly on the photocopying market, ignored the dissenting voices in its ranks, and as a result you’re probably reading this on an iMac, iPad, or MacBook, and not on the non-existent iXerox.

If poor decision-making of this calibre is possible at the highest levels of the corporate world, it’s possible anywhere. So how do you protect yourself against it? Luckily, Janis outlined 3 warning signs.

1. Overestimation of the Group, Underestimation of Competition

One of the big lessons that Kennedy learned in the wake of the Bay of Pigs invasion was that he shouldn’t have taken the CIA’s report on Castro’s military ineptitude at face value. As it turned out, Castro’s 20,000 soldiers were more than capable of warding off an invasion of just 1,400 poorly equipped exiles with no ground support.

A report that advocates for a brazen assault against an opponent that’s 20 times larger would, in most circumstances, be greeted with incredulity. “Surely a hilariously inappropriate typo has been made here?” the average person would no doubt wonder. But Kennedy trusted that the CIA knew what they were doing and kept silent.

The Kennedy administration also radically overestimated their ability to keep the invasion plan a secret. When the invasion plan inevitably leaked, the administration bizarrely decided that the leak wasn’t a big deal: Should Castro decide that a foreign invasion was something that he wanted to defend against, the invading force could just flee to the mountains. Once they were in the mountains, it was assumed that they would be assisted by Cuban farmers and peasants desperate to overthrow the Castro regime. These assumptions, it was soon discovered, had zero foundation in reality.

2. Close-mindedness

The other big lesson that Kennedy learned was that he shouldn’t have ignored the handful of advisors who warned him that the plan was a terrible idea. “At one stroke you would dissipate all the extraordinary good will which has been rising toward the new Administration through the world. It would fix a malevolent image of the new Administration in the minds of millions,” one of Kennedy’s advisors, historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., wrote in a memo (which Kennedy later admitted “will look pretty good when he gets around to writing his book on my administration.”)

Senator J. William Fulbright also voiced these concerns during a presentation to Kennedy’s cabinet. But rather than invite his cabinet to address Fulbright’s points, Kennedy decided instead to move on to the next order of business and pretend that Fulbright’s presentation never happened.

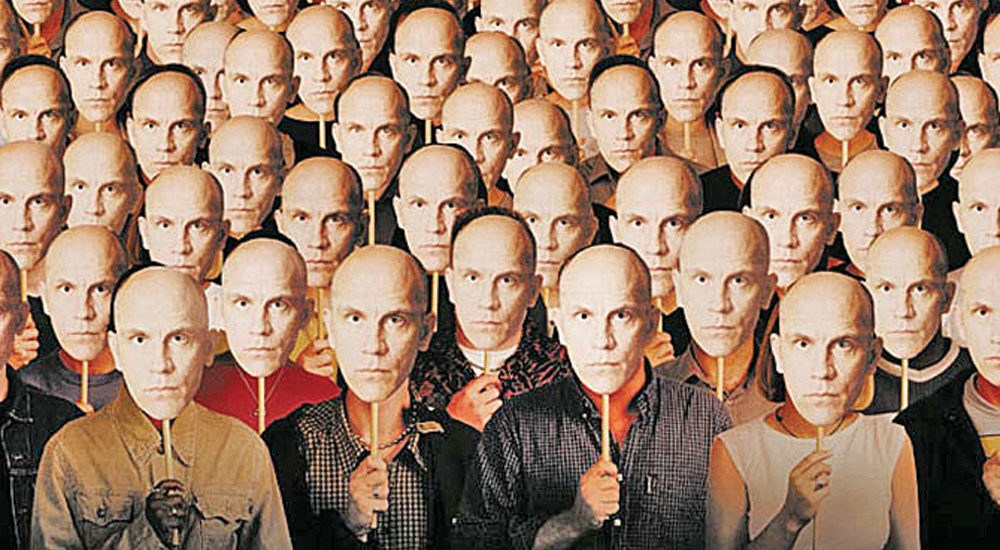

3. Pressure Toward Uniformity

The reason Schlesinger voiced his concerns in a memo rather than during a cabinet meeting was the same reason that many teenagers cite for smoking cigarettes: peer pressure. Kennedy had cultivated an atmosphere in which group consensus was highly valued and Schlesinger didn’t want to be the one to spoil things. ”I can only explain my failure to do more than raise a few timid questions by reporting that one’s impulse to blow the whistle on this nonsense was simply undone by the circumstances of the discussion,” he later wrote. “Our meetings took place in a curious atmosphere of assumed consensus.”

One year later, Kennedy applied some of the lessons he learned from the Bay of Pigs to the Cuban Missile Crisis. He no longer underestimated Castro, listened to his advisors, and deliberately went out of his way to make sure that all dissenting voices were heard. In so doing, he successfully managed to prevent nuclear armageddon, thus allowing Xerox, Kodak, and Excite to make their terrible business decisions in an environment not teeming with deadly nuclear radiation.

Since the publication of Janis’ book, other psychologists and researchers have called some of his claims into question. But even so, it’s probably safe to say that if the most common sentences spoken during your business meetings are, “We’re invincible” and “Apple won’t know what hit them” and “I agree” and “Let’s not hire a consultant,” you may want to take a closer look in the mirror.

Additional Reading

Is Your Business Being Held Back By Groupthink?

6 Steps For Avoiding Groupthink on Your Team

Don’t Let Groupthink Take Down Your Company